Renaissance Man

Lionel Wendt – creator of a truly Sri Lankan idiom

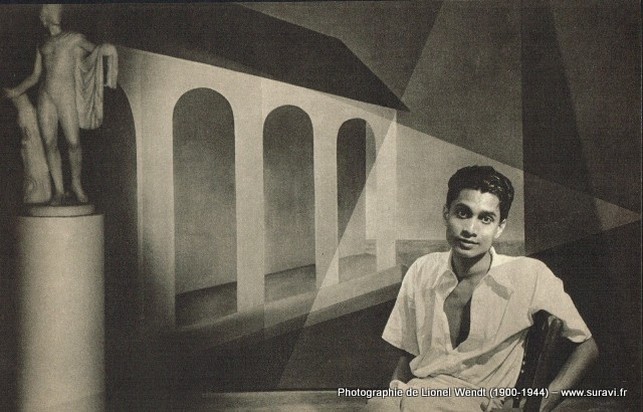

By Ellen Dissanayake

THERE are many people who can impress a listener with their brilliance and discernment, but only a rare few who make those with whom they converse feel that their own ideas are interesting and worthwhile as well. Such a person is excellent and desired company anywhere, and all the more invaluable in places where the time has come for new directions and new ideas and – most essentially – a climate in which to develop these. Such a place was pre-independence Ceylon in the 1930's and 1940's, and such a person was Lionel Wendt.

Today in Colombo everyone knows the name, through the Lionel Wendt Theatre and Art Gallery, but only a few Sri Lankans, those of his generation (he was born in 1900), are aware of the notable achievements and personality of the man himself. A first-rate photographer, pianist, writer, raconteur and wit, teacher, patron of the arts, and of friends, Lionel Wendt was one of those remarkable people that occasionally turn up in times of need. He seems to have impressed everyone who met him – from Pablo Neruda, the Chilean Nobel Prize winner who in the 1920's was a diplomat in Colombo, to Basil Wright, the brilliant British film director whose Song of Ceylon (1934) is one of the landmarks in documentary film history.

Certainly the Ceylonese who had the good fortune to know him, now speak of him only in superlatives. “He was like champagne to his friends,” said one recently, when I asked him to tell me about Lionel Wendt. “If he had lived somewhere else he would have been a world figure – like Oscar Wilde, perhaps,” said another, with unmistakable adulation. “I love to talk about him. It brings it all back.”

TEMPLE OFFERINGS

Wendt was of Dutch burgher background. That is, his parents were descendants of Ceylonese-Dutch intermarriage during the period of Netherlands dominion (mid-17th to early 19th century). The influence of the Dutch in Sri Lanka remains today in architecture, gastronomy, the legal system, a number of words in the Sinhalese language, and in the distinctive personalities and accomplishments of many of their descendants. (The recent Booker Prize recipient, novelist Michael Ondaatje, is one of these.)

In the British colonial period the Dutch burghers, with their Western and Christian background, were often chosen and groomed by the British civil service and commercial establishment to assume responsible posts in government and business. On the whole they were better educated (many of them in England) and more prosperous than other Ceylonese of the time – perhaps as archetypically “bourgeois” as their forebears in 17th century Holland and certainly as Victorian as their contemporaries in fin-de-siècle Britain. To learn about Lionel Wendt and his times is to become acquainted with a world that is fascinatingly different from post-independence Sri Lanka.

Lionel Wendt's father was a judge in the Supreme Court, and his mother the daughter of the district judge in Kandy. It is not surprising that at the age of 19 he was sent to London to study law for the bar. Already at that time an accomplished pianist, he also studied piano in London with Oscar Beringer at the Royal Academy of Music, although it was understood that music could be only a sideline to a “recognized profession”.

WENDT qualified at the Inner Temple as a barrister and practised at the bar in Colombo for a short time. According to one informant his “large and tender heart” made him constitutionally unsuited for the profession and so, having obliged his family's expectations, he gave up practising law and returned to practising the piano. From his mid-twenties he devoted himself seriously to music.

He became a conspicuous figure in what was undeniably the only genuinely “arty” circle of the period, and with his friends – including the painter, George Keyt – sported unconventional clothes (wide hats and floppy bows) and long hair. They read Swinburne, Beardsley and Wilde, as well as more modern Western authors: Shaw, Wells, Bennett.

In his autobiography, Memoirs, Pablo Neruda wrote that:

“Lionel Wendt, who owned an extensive library and received all the latest books from England, got into the extravagant and generous habit of every week sending to my house, which was a good distance from the city, a cyclist loaded down with a sack of books. Thus, for some time, I read kilometres of English novels, among them the first edition of Lady Chatterley's Lover, published privately in Florence.”

Yet Neruda also noted that Wendt “was the central figure of a cultural life torn between the death rattles of the Empire and a human appraisal of the untapped values of Ceylon.” It has been suggested that Wendt's increasing interest in photography during the 1930's was a response to his growing desire to articulate and express the values and life of Ceylonese people. L C van Geyzel in his 1950 introduction to the posthumously published collection of Wendt's photographs, wrote:

“The values of Western culture, dominant for centuries, seemed to need revitalising. Here to hand in Ceylon was a way of life that was very old, but which retained in spite of poverty, squalor, and apathy, a vital sense that was lacking in more progressive countries. Man, living in traditional ways, had not become alienated from his environment. It is this which [Wendt's work] so richly illustrates.”

Along with the affected pre-Raphaelite poses and bicycle-loads of modern European literature, Wendt and his friends were trying to find – or make – a new national identity or national consciousness. The old Wine of Western civilization need not be thrown away, but should be imbibed from the clay jugs of rural Ceylon, acquiring an authenticity and relevance to the traditional situation.

To Wendt and his contemporaries in Colombo, rural Ceylon was about as foreign and exotic as Tahiti had been forty years earlier to Gauguin. Yet they seemed to feel in their bones that their future, and the country's future, lay neither in ignoring the ancient heritage nor repudiating Western ways, but in absorbing and responding to what they could of both and somehow amalgamating them.

This recognition was almost unconscious and for a time they seemed to be simply using Ceylonese subject matter in styles appropriated from the contemporary West. Always, however, the beauty and power of rural Ceylonese life was made manifest and in the best work of the period (for example in Wendt's photographs and Keyt's paintings) the Western adaptations were always those which echoed or reinforced the older Indo-Ceylonese tradition.

Wendt's contribution to modern painting in Sri Lanka cannot be overstressed. It was he who made available to aspiring artists prints of contemporary European artists, along with new books, from England. He bought paintings by the young W J G Beling, George Keyt, and others, organized exhibitions, and defended these publicly in the newspapers with witty and incisive replies to hostile critics and suspicious, uncomprehending viewers.

AT THE POTTERY

The '43 Group which essentially introduced and maintained modern art in pre- and post-independence Ceylon was the creation of Wendt, whose organizational skills brought to actual realization the half-intentions and good ideas of the artists. Over a period of 25 years (1943 to 1968) the '43 Group exhibited publicly, thereby providing an atmosphere for younger painters to develop and a climate for an appreciative audience to grow. Although Wendt died a year after the '43 Group held its first exhibition, no-one disputes the catalyzing effect of Wendt at its inception. In fact, as late as 1955, eleven years after his death, a snidely dismissive newspaper review of the ninth '43 Group exhibition claimed that “everywhere that Lionel Wendt the lambs were sure to go” – implying that it was Wendt's influence, energy, and prestige that gave the group its cohesion and life.

Wendt's achievements in photography alone are extraordinary. He experimented with solarised prints as early as 1935, which was perhaps one of the earliest uses anywhere of the solarisation effect for pictorial ends. He entered (and was accepted by) numerous international photographic exhibitions, often with two different styles under two different names. In 1938, Messrs Ernst Leitz, manufacturers of Leica, arranged a one-man exhibition of his work in London. His book of photographs, Lionel Wendt's Ceylon (London: Lincoln's Praeger, 1950) with a first edition of 5000 copies, is now a prized collector's item.

IN 1934 the British Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board engaged John Grierson's GPO Film Unit to produce a film about Ceylon as a public relations enterprise. The resulting picture, Song of Ceylon, went on to receive first prize for documentary at the Brussels International Film Festival in 1935, and is given accolades in all accounts of documentary film history. The film is remarkable for unusual uses of the soundtrack as well as the imaginative montage and pictorial effects of director-cameraman Basil Wright.

Before he died in 1987 at age 81, Wright recalled that before setting out on the project he hoped to find help from a “non-colonial mentality”:

“Luckily, the head of the Board, G K Stewart, was an enlightened character, explained Lionel's burgher origins to me, and arranged for us to meet [at the Grand Oriental Hotel in Galle]. To begin with he was bristling with suspicions, but after a long talk with me and my assistant John Taylor he decided we were OK. He was of course invaluable throughout, and… guided us splendidly through the making of the film.”

While editing the film in London, Wright found he had metres and metres of (for example) Sinhalese dancing but without synchronized recording apparatus there were no sounds to go with them. He arranged for two Kandyan dancers to come to England with Wendt as their mentor and guide. Apart from providing the background of drums and singing, the dancers trained a church choir from near the studio to produce suitable sounds for the dancing lesson sequence in reel two.

As the film emerged, Wright decided it would be unthinkable to add a travelogue type of commentary, characteristic of “exotic” films of the period. By chance he discovered the classic 17th century account of medieval Ceylon by Robert Knox, a British sailor held in captivity for 19 years by the king of Kandy. The old-fashioned prose seemed eminently suitable, but the actors and broadcasters who auditioned for the voice over made it sound phony. Two days before Wendt's departure from England, Wright idly suggested that he try the narration. It was, according to Wright, “the perfect choice” and thus Lionel Wendt's deep, cultivated voice is preserved in this exceptional film.

Lionel Wendt was a big man, in keeping with his large talent. He had enormous energy, as well, which his friends say infused his entire personality. Everything in his character seems to have been superlative. For all my prodding people to remember evidence of dark corners, no one has had anything but good to say of him. He was “largeheart, but he hated insincerity and hypocrisy”. He was “so learned”, witty (“he had a marvellous way of relating stories, making things look ridiculous”). He “analysed everything through and through”, was “such a personality”. He “was indifferent to his own reputation, but quick to defend other artists”, and “was unforgettable and desired company”. “There was no moment you'd forget. He was a truly great man, honest, sincere, humble, friendly and kind and self-sacrificial.”

A prolific writer of letters, Wendt's fancy ran free, as in this advice to a piano pupil who had cancelled a lesson due to injury:

“I hope you don't strain or even sprain your memory. It will be awkward if you begin to memorize everything – conversations, fugues, birdsongs, wren's chatter, wallpaper, glue, buildings, marmalade, etc.”

To his friends he wrote loose couplets in the manner of Ogden Nash and obviously loved puns and wordplay (a pupil named Hilda became “Bewilda”). Owners of his letters treasure them, not only for their delicious references to long-forgotten scandals but for their memorable way with words and descriptions: “… I can't worry in more than 3-part counterpoint.”

'AND NOTHING SURPRISES ME'

L C van Geyzel, who was one of Wendt's close friends, tells us that he possessed practical and intellectual qualities not often found in artists. He thinks that with his curiosity, taste, and capacity for hard work, Wendt could have been a scholar, but perhaps he also felt that too much intellectual luggage would be cumbersome and interfere with immediate aesthetic perception.

Wendt's home reflected his interests and personality. In a long sitting room with low bookshelves on grey walls were hung paintings by his friends in frames he had himself painted and designed and enormous enlargements of his own prints. And there was his grand piano. In 1929 Beling and the German painter, Otto Scheinhamer, side by side, each painted Wendt's portrait, wearing a dressing gown and seated at the piano. The Beling picture hangs today in the Lionel Wendt Memorial Theatre.

Any country would welcome such a multitalented, multifaceted native son whose gifts, as it turned out, were as much for encouraging and enlarging the experience of others as for self-development. His premature and unexpected death (of cardiac asthma) shortly after his 44th birthday, nearly a half-century ago, ended a life of contributions to others and personal fulfilment that would be enviable in a normal life span.

Writing of Wendt, van Geyzel sums up (if such a thing were possible) his unforgettable friend:

“But there was something over and above and more profound; a self-sufficiency that was neither selfish nor ingrown, and an assurance that was never arrogant, or in the slightest degree pompous (a healthy irreverence indeed, was one of his most delightful characteristics). These qualities claimed one's confidence and made one always want to share one's experiences with him. If at times he could be exasperating he was never insincere, and he had breadth of character that made temporary irritations seem quite unimportant. Such personalities are rare. They are so vivid that they seem in some special way to belong to life itself.” □

Dissanayake , E. (1994). Renaissance man: Lionel Wendt – creator of a truly Sri Lankan idiom. Serendib, 13(4), 16-22.